Early Baseball “Cranks” and “Fans” - KCQ Touches All the Bases in This Investigation

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Jeremy Drouin| lhistory@kclibrary.org

With the Major League Baseball season underway and the Royals faithful cheering on their boys in blue, it is fitting for What’s Your KCQ? to get a curveball about a possible KC connection regarding the origin of baseball “fans.”

While flipping through a 1990 publication, On This Day in America, a reader came across an entry for March 26, 1889, that credits The Kansas Times and Star with referring to followers of baseball as “fans” for the first time. The reader asked KCQ to investigate whether it was true and if the newspaper referenced actually was The Kansas City Star or Times.

Before T-shirts are printed promoting Kansas City as “Home of the Original Fans,” let’s look into the claim more closely.

The Library of Congress’ Directory of US Newspapers in American Libraries has no record of a Kansas Times and Star. However, there were other late-19th-century papers with similar titles. The Kansas Times, first published in 1879 in Osage, Kansas, became the Lyndon [Kansas] Journal in 1882; and The Kansas Star was published from 1890-1901 in Wichita.

Since neither was published in 1889, perhaps “fan” was first introduced in The Kansas City Star or its competitor at the time, The Kansas City Times. A search of the two dailies for March 26 found no mention of baseball fans. However, baseball news of the day was reported.

The major announcement was a meeting of representatives of the city’s amateur clubs the previous evening at The Star’s offices. The purpose was to organize a city league that would guarantee a schedule of games and “ensure discipline and instruction in the points of play.”

In this era, numerous amateur teams played in city leagues and traveled to neighboring towns to challenge their best “nines.” Many teams were sponsored by local businesses and athletic clubs and went by such names as the Schmelzers, Golden Eagles, KC Stars, and Manhattans.

Clothing House was an early supporter of local baseball, sponsoring an

amateur team that was dominant for many years in city leagues.

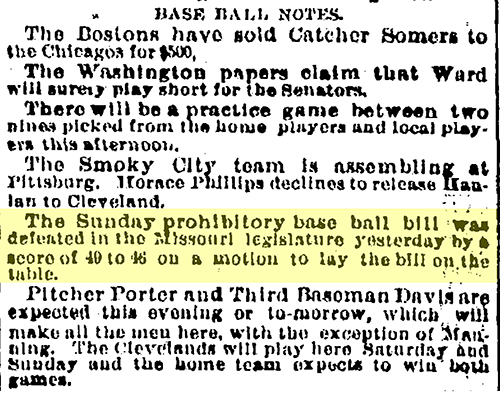

Also of interest was a blurb under “Base Ball Notes” that the Missouri legislature had narrowly rejected a measure to prohibit the playing of baseball on Sundays, surely to the chagrin of churchgoers throughout the state. While routine today, Sunday games stirred considerable controversy in the 1880s.

According to the online Merriam-Webster dictionary, “In English, fan made an early appearance in the late 17th century only to disappear for two centuries, resurfacing in the late 19th century. In this later period of use, it often referred to the devoted observers of, or participants in, a sport. An 1885 article from The Kansas City Times, for example, contains the line “The base ball ‘fans’ of the ploice [sic] force and fire department engage in a ball game.”

The entry does not claim that “fan” was introduced or popularized by The Times, but it is noteworthy that another source references its use in a Kansas City newspaper.

Cranks, Fiends, and Rooters

Baseball in the 1880s was a raucous game that in turn attracted its share of rowdy spectators. Drinking, gambling, and cursing were prevalent, and umpiring was a hazard, especially if calls went against the home team. The game – albeit growing in popularity – suffered from a low-class image.

Newspaper writers used derogatory terms such as “cranks,” “fiends,” and “bugs” to describe baseball enthusiasts.

The Kansas City Times, commenting on a Sunday game played in Kansas City.

A Topeka correspondent’s experience at a Kansas City baseball game, published in The Kansas City Star on June 4, 1885, reflects the attitude towards the game’s more rambunctious followers:

“It is unfortunate, however, that there are so many ‘base ball fans’ as the players contemptuously term them, at the games, and that they are unrestrained in their abuse of players, umpires, and those of the audience who venture to remonstrate with them. These ‘fans’ consider themselves better judges of play than any umpire, would teach all the players how to play their positions, and feel that upon their approbation alone depends on the success of the club.”

The reporter went on to describe the “fusillade of hooting, howling, and blasphemy” coming from the stands, which would discourage any respectable woman from returning to the ballpark after witnessing such coarse behavior.

women at baseball games was uncommon enough to warrant coverage in the newspapers.

However, the unruly “rooters” in the stands did not deter some of the city’s more upstanding citizens. Businessmen, physicians, and city officials were among the “regulars” mentioned in a May 20, 1887, Kansas City Star story about local baseball lovers.

Law enforcement officers were so prevalent at games, it was joked that the “ball players must be hard characters … to have so many detectives watching over them.” The article also noted that while Protestant ministers were to stop frequenting games after the church proposed a ban on Sunday play, a few remained among the regular spectators.

Numerous references to baseball “fans” were found in The Kansas City Star and Times beginning in 1885. Could this be earliest use of the word in relation to the game? Baseball historians point to an earlier source.

Godfather of the National Game

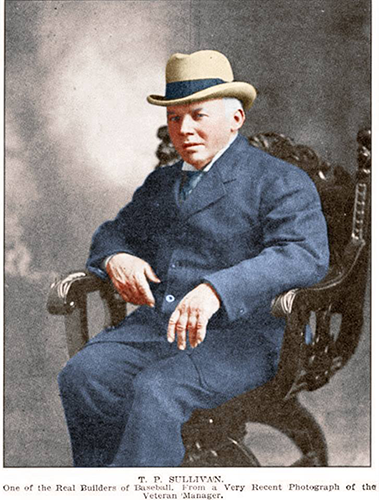

Timothy Paul “Ted” Sullivan was a pioneering figure of 19th century professional baseball. Referred to as “The Godfather” of the game (one of his many titles), he is also credited with coining the term “fan” to describe its most fervent, if not overbearing, supporters.

Sullivan, an Irish immigrant, was an early baseball player, manager, league organizer, and scout during the sport’s infancy in the decades after the Civil War. He formed the Northeast League in Iowa in 1879 and managed the Dubuque Rabbits to a league championship the same year. In 1883, he was recruited to manage the St. Louis Browns of the newly formed American Association professional league.

Colorized by Imbued with Hues.

In his 1903 book Humorous Stories of the Ball Field: A Complete History of the Game and Its Exponents, Sullivan recounts an incident with an obnoxious “crank” who confronted him at the Browns’ headquarters. The man purported to know “every player in the country with a record of 90 in the shade and 100 in the sun,” and pestered Sullivan with “his opinions on all matters pertaining to the ball” until Sullivan called upon his players to have him removed.

When Sullivan wondered what to call “such a fiend as that,” his star first baseman and protégé, Charlie Comiskey (later the founding owner of the Chicago White Sox and namesake of Comiskey Park), proclaimed, “He is a fanatic.” Sullivan responded that he would refer to him as “the fan” whenever he was seen around the headquarters.

If you are skeptical about the details of Sullivan’s account, you’re not alone. Pat O’Neill, a chronicler of Kansas City’s Irish history and co-author of Ted Sullivan, Barnacle of Baseball, noted Sullivan’s penchant for storytelling and spinning various versions of his encounter with the know-it-all fan with one detail unchanged – it was he who first came up with the term.

In a different account, Sullivan complained to St. Louis Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe about the team’s meddlesome board of directors, referring to them as fanatics or fans.

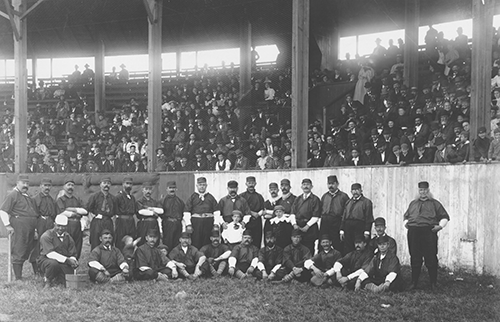

Charles Comiskey is standing far left; team owner Von der Ahe is in the center.

Another story, reported in The Boston Globe in 1911 and highlighted in O’Neill’s biography, traces back to Sullivan’s earlier managerial stint with the Dubuque Rabbits. Sullivan reportedly commented on the tobacco-smoking “hayseeds” who would gather in the team hotel lobby, “fanning us with that hot air.” The “fanning hayseeds” moniker became “fanning bees,” ultimately leading to the abbreviated fans.

Despite numerous versions of the “fan” origin story, Sullivan is generally accepted by baseball historians as the term’s originator. By coincidence or not, it was shortly after Sullivan took over as a manager of Kansas City’s first professional baseball team in 1884 that references to “fans” began to appear in the local newspapers.

The Kansas City Unions

Sullivan had left the Browns in the middle of the 1883 season after a dispute with Von der Ahe and took over as manager the St. Louis Maroons of the upstart Union Association.

The eight-team Union Association formed in 1884 as a rival of the National League and American Association. Kansas City joined the league 25 games into its inaugural season when the Altoona, Pennsylvania, franchise folded due to financial difficulties, giving the city its entrée to the professional game.

baseball game against the Chicago Unions, a 6-5 loss. The Kansas City Evening Star, June 9, 1884.

On the other side of the state, Sullivan’s Maroons started that season on a 21-game winning streak. But a fallout with the team owner led to him joining the Kansas City Unions midyear as manager and partial owner (he even played in three games). The Kansas City club finished at the bottom of the standings with a 16-63 record, while Sullivan’s former team in St. Louis won the league title.

The Union Association disbanded at the end of the 1884 season when too few owners showed interest in keeping it going.

Determined to keep baseball in Kansas City, Sullivan and other team owners reached out to other cities to form a new league. The following year, the Western League was founded with Sullivan managing the Kansas City team (nicknamed the Cowboys).

The season got off to a promising start on April 18, 1885, with Kansas City beating the Omaha club 12-4. But the Western League proved to be unsustainable and disbanded before a full season was played.

Sullivan would leave Kansas City to take a position as manager in Memphis in the newly established Southern League. He remained in active as a manager, scout, and promotor until his death in 1929.

Colorized by Imbued with Hues.

Professional baseball survived in Kansas City, with fans supporting teams such as the Cowboys, Packers, Blues, Monarchs, Athletics, T-Bones, and of course our beloved Royals.

The Final Word

The assertion that “fan” was first used in a March 26, 1889, Kansas or Kansas City newspaper is unfounded. One can search sports sections prior to 1889 and find numerous mentions of baseball fans.

While Sullivan was a legendary storyteller, and one account of him coining the word in 1883 was published 20 years after the fact, baseball scholarship generally supports his claim.

“Whether or not he was the first to utter it, I can't say,” says O’Neill, the local historian and author. “But certainly he is the one who claimed it for his own and who ‘put it in play’ with the newspaper scribes.” This is supported by the many printed references to “fans” while and where Sullivan was managing.

The term has stood the test of time since it was first used in a baseball context in the 1880s. It has become part of the American lexicon, evolving to describe devotees and enthusiasts beyond the world of sports.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.