Is it true that missiles were buried near Kansas City? KCQ answer reaches for the sky

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Randy Mason | tvdrmason@gmail.com

The Cold War years were fraught with tension. It was a time of global gamesmanship and military staredowns.

And it sets the scene for a question that Kenneth Goodwin submitted to “What’s Your KCQ?” He asked if it was true that ballistic missiles had been buried along Van Brunt Boulevard near Linwood Boulevard in the early 1960s.

It sounded unlikely. But those were strange days. So we checked around. Military and government records, old newspapers. No sign of nukes on Kansas City’s East Side.

James Stemm, director of collections at the Titan Missile Museum in Green Valley, Arizona, confirmed that if nuclear weapons were ever there, “the Army and Navy didn’t know about them.”

But he pointed out there were some stashed nearby.

For years, ICBM silos dotted the countryside around Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri and Forbes Air Force Base near Topeka. They held powerful Titan II and Minutemen missiles, the kind that scared everyone in the 1983 movie “The Day After.”

Eventually, those installations were phased out and relocated to more remote spots across Wyoming and the Dakotas. As that chapter in the Cold War ended, it brought opportunities for creative use of the underground spaces left behind.

In 2015, The Star chronicled one such entrepreneur, Russ Nielsen, excavating a silo he’d purchased near Holden, Missouri.

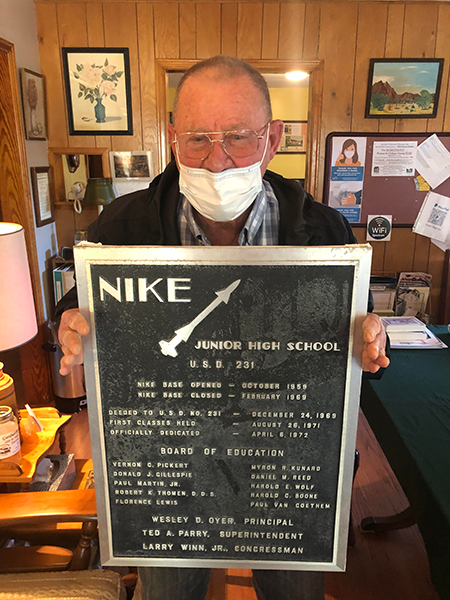

Now, Nike Elementary School carries the name. Credit: Gardner Historical Museum

‘Armed with nuclear warheads’

But an earlier generation of missiles — the Nike-Hercules, once crept even closer to the edge of the metro. These were, according to Stemm, “armed with nuclear warheads.”

Here’s the deal. By the late 1950s, as tensions with the Soviets grew, cities across the country sought ways to fortify themselves. One such result was the creation of the Kansas City Defense Area in 1959.

It included four bases armed with Nike missiles — Pleasant Hill and Lawson to the east, with Fort Leavenworth and Gardner on the Kansas side. A command center operated out of the Olathe Naval Air Station.

Unlike ballistic missiles, the Nikes were not launched from silos. They were essentially anti-aircraft installations whose nuclear payload could take out incoming bombers or missiles, even without a direct hit. Stemm likened the concept to the old video game “Missile Command.”

Gardner resident Joe McNulty remembers hearing from a farmer whose land adjoined the launch site that he’d been told “if we have to use them, you’re already in bad shape.”

Luckily, they never had to.

The Nikes weren’t around very long. By the mid-60s defense strategies had changed dramatically, and by decade’s end the missile sites had all been deactivated. Some, like the facility at Fort Leavenworth, were repurposed. It’s now a gun club.

In 1969, the Gardner School District bought the operations portion of the base (the actual launch site is a mile further south) to solve their need for a new junior high. They christened their rambling assortment of buildings off Moonlight Drive Nike Junior High.

McNulty, who taught math and coached at the school helped choose a name for their mascot.

What else? The Missiles.

This light-hearted link to a dark past seems to have stuck. Thirty years after the Cold War ended, Nike Elementary School sits on the junior high’s old site. And inside, a new generation of Missiles is still “reaching for the sky.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.