From Top to Bottoms: Your KC Q Answered

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. The purpose is to help Kansas Citians become more knowledgeable and informed citizens. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Question

Reader Wayne Moots recently asked us how people used to travel up and down the rocky bluffs that separate downtown from the West Bottoms. Moots works at the revitalized Golden Ox restaurant, and has had plenty of time to ponder this KC Q during his commute.

The Answer

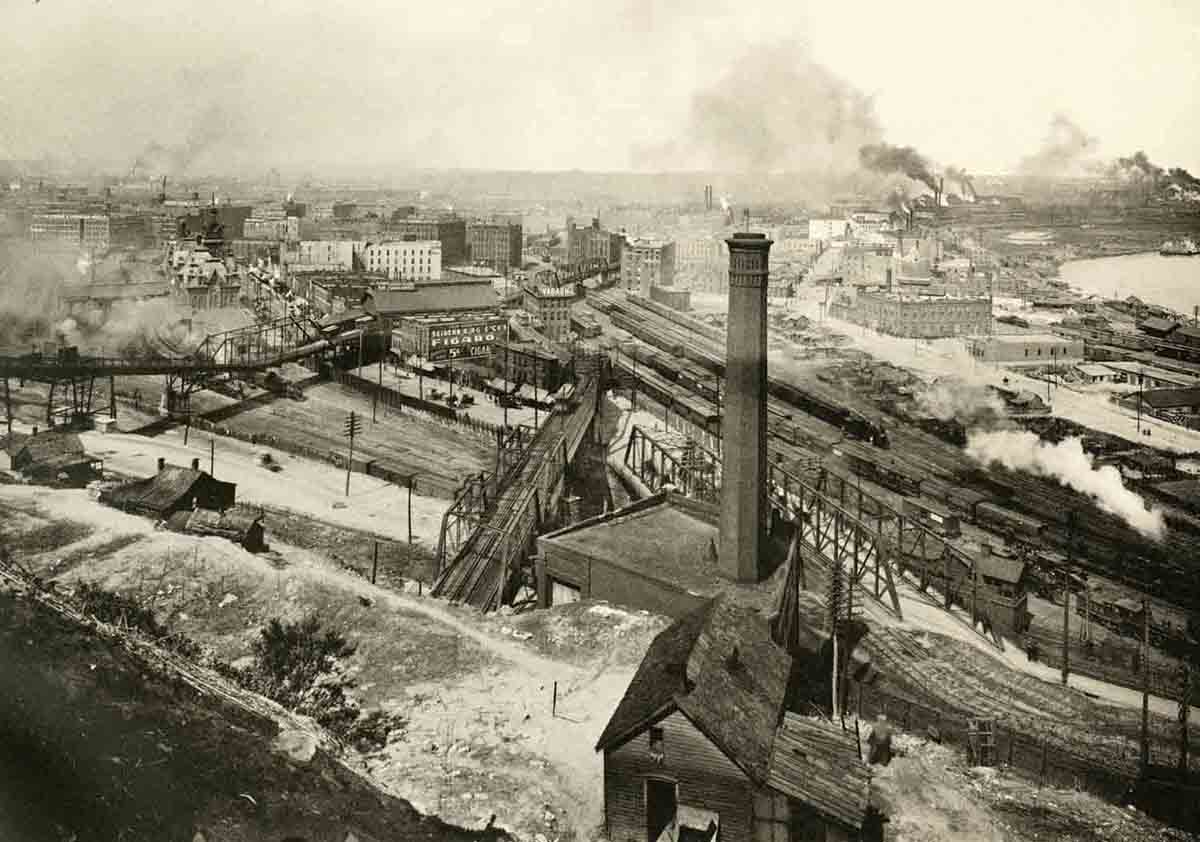

Prior to the automobile boom, many Kansas Citians relied on public transportation or merely the power of their own two feet to get them from place to place. With downtown serving as a business hub and a variety of bustling neighborhoods surrounding it, some means of reaching industry and jobs in the West Bottoms was a necessity. Moreover, Union Depot, the city’s first major passenger rail hub, was situated at 9th Street and Union Avenue near the foot of the bluffs.

Streetcars and buggies heading downtown from the West Bottoms near the bluffs, 1900. Kansas City Public Library

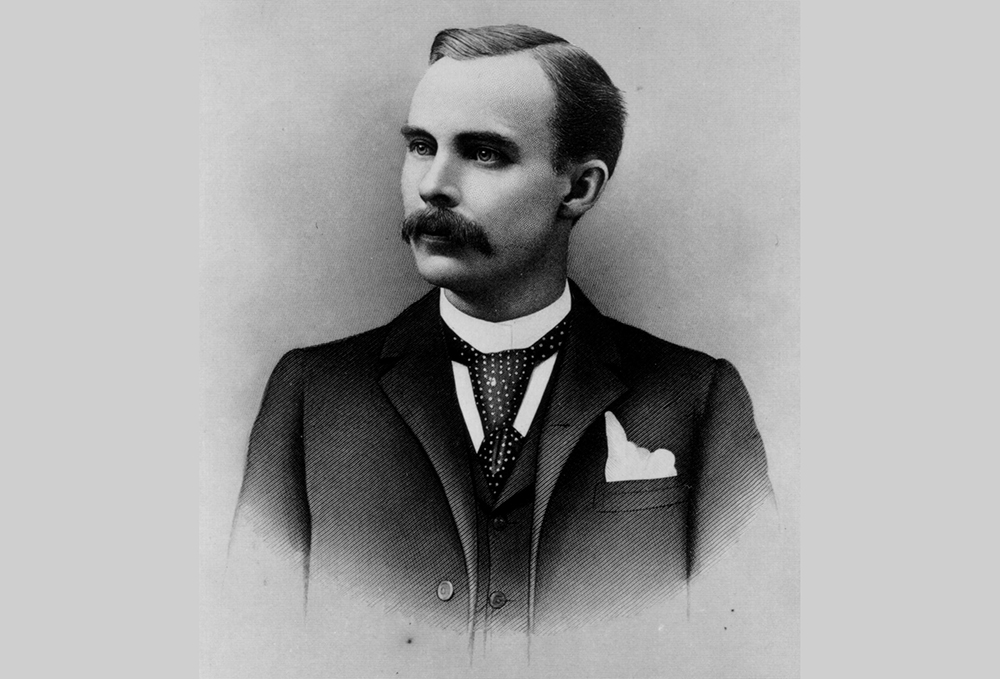

An early effort to get rail passengers to and from Union Depot and commuters to and from the West Bottoms was conceived in the late 1870s by civil engineer Robert Gillham. Gillham had recently relocated to Kansas City from the East Coast, and saw the bluffs as a worthy challenge. At that time, the only transit route connecting downtown to Union Depot required passengers to ride a horse-drawn streetcar, or “hayburner,” north along Main Street, west along 5th Street around the bluffs, and back south again to finally reach the station. Gillham proposed a radical change, an elevated cable car line along 9th Street, running straight over the bluffs.

Mule-drawn, or “hayburner,” streetcar in a parade celebrating the introduction of streamliners to Kansas City, 1941. Kansas City Public Library

Following Gillham’s initial proposal in 1879, he and his investors organized the Kansas City Cable Railway Company in 1883. The first cable car traveled up the incline on June 15, 1885. Operations went smoothly at first, but a problem associated with the ramp’s impressive 18.5 percent grade soon became apparent. On its second day of operation, a group of nervous dignitaries bailed out of the cable car at Jefferson Street just before it made its steep and sudden drop, the car’s crew and a single brave newsboy safely arriving at their destination moments later. Gillham’s bridge was not for the faint of heart.

View of the Ninth Street Incline from the West Bottoms, 1895. Kansas City Public Library

In direct competition with Gillham’s 9th Street route was the Metropolitan Street Railway’s 12th Street Incline. Completed in 1888, riders had to endure an even steeper 20 percent grade during trips to the bottom of the hill. The line ran until 1913 and had an impressive safety record despite its daring design.

Final streetcar trip over the 12th Street Incline, 1913. Kansas City Public Library

Although mishaps did occur on the Ninth Street Incline, it did operate without a fatal accident for many years. During a routine trip in 1902, however, a two-car train preparing to descend the bluffs slipped from the cable controlling its descent and plummeted down the hill and into another train. Only a few passengers were seriously injured, but one member of the runaway train’s crew perished. Though there was outcry for the ramp’s immediate closure, the Metropolitan Street Railway Company, which had assumed control of the line in 1895, lacked a viable alternative for moving customers between downtown and the West Bottoms and decided to keep service running. Its officials would have to wait for work to be completed on another of Gillham’s daring plans.

Undated portrait of Robert Gillham, designer of the Ninth Street Incline and later the Eighth Street Tunnel. Kansas City Public Library

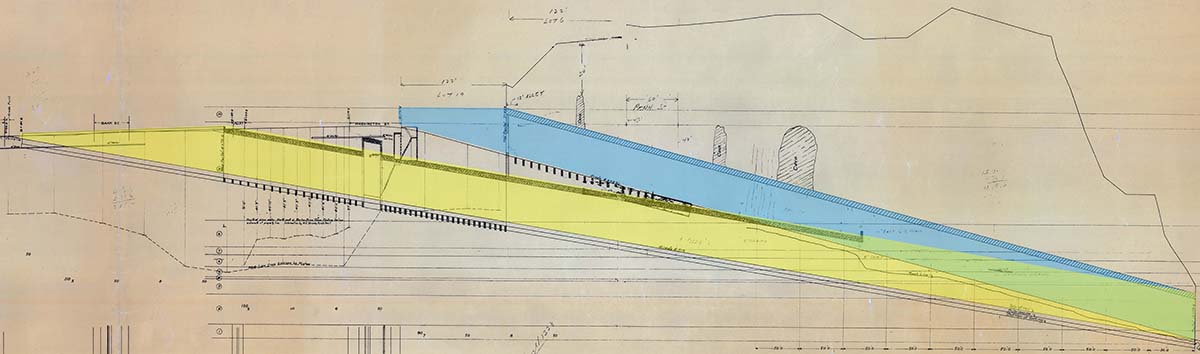

Construction on his first Eighth Street tunnel began in 1887, just two years after the Incline was opened. The logistics of drilling through the bluffs was considered audacious at the time, but Gillham theorized that the work would pay off by because the line could travel at a more comfortable grade. The first tunnel began at the base of the bluffs and exited near Jefferson Street, which put it at a modestly lower grade than the 9th Street option.

View looking down at the West Bottoms from Quality Hill showing the Ninth Street Incline and Eighth Street tunnel entering the bluffs, 1899. Kansas City Public Library

It opened for service in 1888, and operators swiftly realized that the grade still left something to be desired. Plans to redesign the tunnel were drawn up, and work began in 1903 to extend its exit to close to Broadway and reduce the grade to an acceptable 5.5 percent. The clock was ticking for the Ninth Street Incline. Tunnel work was completed in 1904 and on April 6 of that year, cable cars made their final trips up and down the tracks. The Ninth Street Incline was closed off and demolished the following year.

Diagram showing the Eighth Street tunnel with the original route highlighted in blue and the redesigned route in yellow, 1903. Kansas City Public Library

A final note concerning the Incline: Despite its flaws, Gillham was meticulous in his plans, making sure to include a staircase stretching from Quality Hill to the foot of the bluffs. This option would come in handy over the years, offering a walking option during lapses in cable car service or for those reluctant to part with a fare.

The Ninth Street Incline with staircase leading from Quality Hill down to Bluff Street, 1895. Kansas City Public Library

Alternate footpaths were available to pedestrians. From downtown, it was possible to walk along 5th or 6th Street to the Bluff Street Bridge and over to Union Avenue in the West Bottoms.

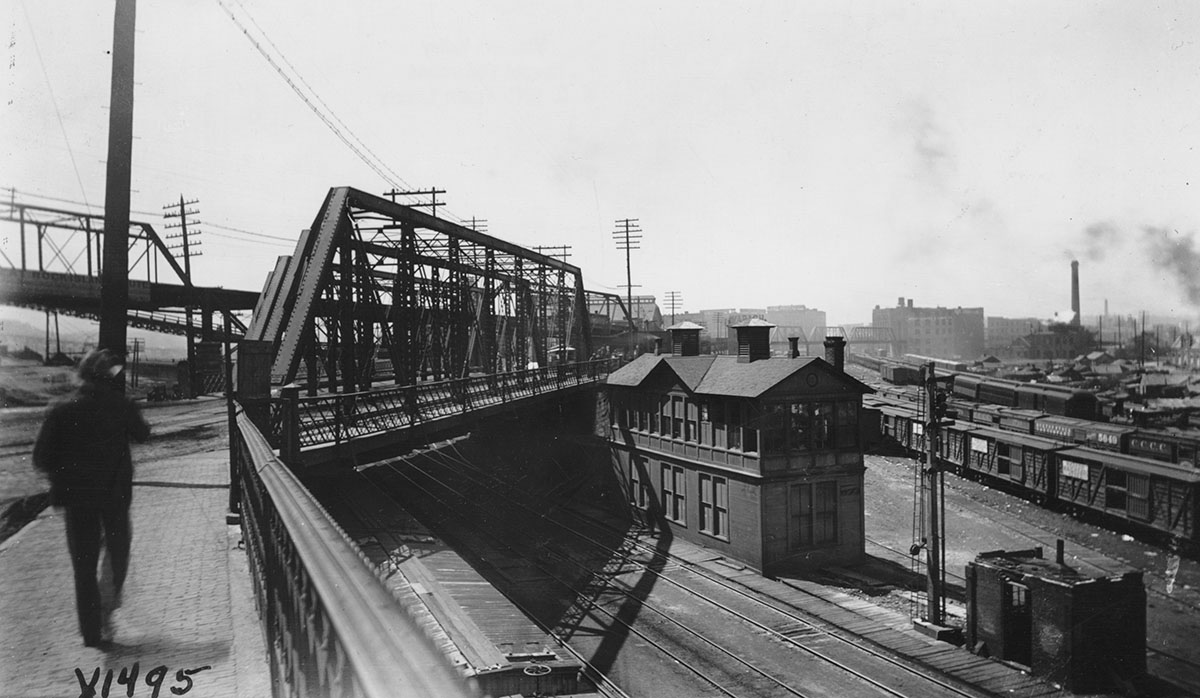

A pedestrian preparing to cross the Bluff Street Bridge into the West Bottoms, 1894. Kansas City Public Library

Also, long before the area was redeveloped as a park and then cleared to make room for Interstate 35, many small homes lined Bluff and Lincoln streets between Quality Hill and the West Bottoms. Not willing to wait for modern sidewalks, residents of the area wore an assortment of well-trod trails up and down the hill.

View facing east near the 12th Street Incline and showing pathways connecting the residences on the hillside down to Bluff Street, 1900. Kansas City Public Library

Long dissatisfied with the shack-dotted hillside greeting arriving visitors at Union Depot, city officials began planning a park along the bluffs in the early 1890s. Following lengthy legal challenges from property owners and hillside residents, West Terrace Park was opened in stages beginning in about 1900. The park’s centerpiece was a massive, stone tower-capped retaining wall with a staircase leading to a secluded grotto and the new Kersey Coates Drive. The new road served as a scenic path along the bluffs until the 1960s, when the western end of the Downtown Loop pushed through and divided the park.

View of the grotto once located adjacent to Kersey Coates Drive in West Terrace Park, 1933. Kansas City Public Library

While it is true that much of downtown’s connectivity with the West Bottoms was disrupted by I-35, it is worth noting that adventurous pedestrians still can make their way between the two areas using the 12th Street Viaduct or by following in the footsteps of earlier Kansas Citians. By skirting the bluffs through the River Market, it’s possible to connect to Beardsley Road. From there, it’s a short walk down into the West Bottoms. Ironically, the route is nearly identical to the old, out-of-the-way, horse-drawn streetcar line that inspired Gillham to first build over and later bore through the bluffs.

How We Found It

Historical information related to the development of Kansas City’s transit infrastructure was found in Monroe Dodd’s book, A Splendid Ride: The Streetcars of Kansas City, 1870-1957 and James Shortridge’s Kansas City and How it Grew: 1822-2011, both available for checkout from the Kansas City Public Library. The featured photographs can be found in the Missouri Valley Special Collections on the fifth floor of the Central Library. Additional details came from an October 13, 1953, article in The Kansas City Times, "Hair-Raising Ninth Street Incline is Recalled by Cable Car Anniversary."