‘His history is notorious’: KCQ tracks mafia connections at Northland country club

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

If you are familiar with Kansas City’s violent mafia history, you know the names Charlie Binaggio and Nick Civella.

But Eddie Osadchey?

Doesn’t sound like a mobster’s name, does it? In fact, to a grade-school boy overhearing his father’s conversations in 1963 or so, the name evoked visions of the family’s many Irish acquaintances. O’Brien, O’Neill, O’Satchy?

So no alarm bells went off when my father said he was doing some bookkeeping to help out his friend Eddie Osadchey, who ran the neighborhood country club we frequented. My dad, William J. “Bill” Kelly, worked for TWA, always describing his job as accounting, and he didn’t mind lending a friend a helping hand.

Only in this case, his hand might have been dipping into some hot water.

Osadchey — better known as Eddie Spitz in those days — had been as mobbed up as they came in Kansas City during the 1940s, serving as one of boss Binaggio’s key operators (until Binaggio and Charlie Gargotta were gunned down on April 5, 1950). By the 1960s, Civella had taken over as local boss, and Osadchey was linked to him, too.

The story of Eddie Osadchey is key in responding to a question to “What’s Your KCQ?” from Richard Taegel. “What’s Your KCQ?” is an ongoing series in which The Star and the Kansas City Public Library partner to answer readers’ queries about our region.

Taegel’s query, edited for length:

“Can you explain the nefarious existence of the Mirror Lake Town and Country Club? … I heard rumors at the time that the club had some connection with the greater Kansas City mob scene. … And whatever became of Mirror Lake after the ’60s?”

Those mob rumors were true.

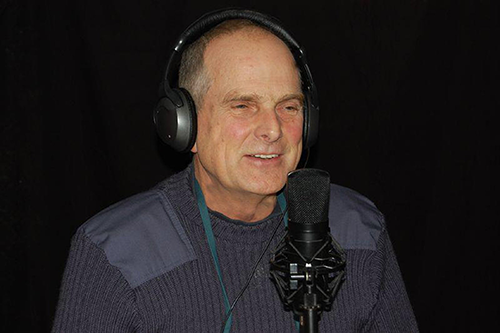

“Osadchey goes way back, had a lot of connections and all sorts of the early history of the outfit,” William Ouseley said recently.

Ouseley ought to know. He not only worked the local mob for the FBI from the 1960s through the 1980s, he also has written two books about it (Open City: True Story of the KC Crime Family, 1900-1950 and Mobsters in Our Midst: The Kansas City Crime Family).

“In gambling, he was one of the primary movers and shakers for the mob even though he was not a member, being non-Italian. But he was a very trusted person.

“He was a principal guy who put together the (horse racing) wire service for (Al) Capone’s people representing the mob here. It was their franchise. His history is notorious.”

KC Mafia?

Turns out the Taegels (eight kids) lived only a few blocks from the Kellys (four kids) in Sherwood Estates, then a relatively new subdivision in the Northland. Taegel, like me, attended St. Gabriel, the Catholic grade school that was within walking distance of our homes and happened to sit right next to the club in question.

With just a swimming pool and a clubhouse, it was called the Sherwood Estates Country Club when our family moved there in the late 1950s, but it became the Mirror Lake Town Club when Osadchey bought it in 1961. He already owned the Mirror Lake Country Club, which had a golf course and a fishing lake, a few miles away near Parkville.

Young Richard Taegel indicated he worked at the Town Club starting in 1967, doing odd jobs and busing tables for 50 cents an hour (“For a 14-year-old, I thought that was big money at the time”). Hired by Osadchey’s son and daughter-in-law, Bill and Jane Osadchey, Taegel occasionally landed busing gigs at the Parkville club, too.

To answer his primary question: There wasn’t much “nefarious” about the Mirror Lake Town Club (though the Country Club was a somewhat different matter). According to both Ouseley and fellow local mob expert Gary Jenkins, the Town Club’s Bill Osadchey had no connections to the outfit.

Moreover, by the 1960s, Eddie Osadchey had put his mob activities behind him — although not necessarily his mob relationships.

“He was never a factor during Nick Civella’s reign,” Ouseley said.

“You never heard his name about anything,” said Jenkins, who worked for the intelligence unit of the Kansas City police starting in the 1970s and now is co-host of the “Gangland Wire Crime Stories” true crime podcast.

That’s not to say Eddie Osadchey was a Boy Scout during his Mirror Lake days — he had several legal scrapes. But it was nothing like his life before 1950.

The Kefauver hearings

Osadchey was born in Kiev in 1906. He and his Russian Jewish family arrived in the United States in 1909, with his name appearing as “Avrum Osadzy” on the SS Russia’s passenger list. They immediately settled in Kansas City, where his father worked as a blacksmith.

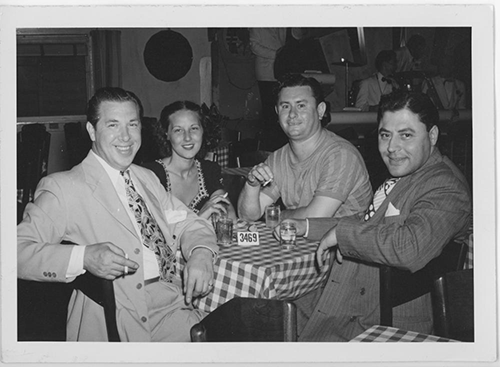

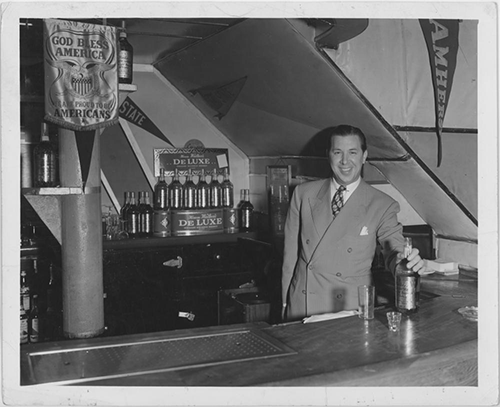

Before and after serving in the Army Air Forces during World War II, Osadchey operated local nightclubs (including the College Inn on 12th Street, Club Imperial on Oak, the Dump on McGee Trafficway and the notorious Last Chance Saloon that straddled the state line). Osadchey also reputedly ran Binaggio’s local gambling operations and was said to be involved in Binaggio’s liquor distribution business (he was sentenced to 30 days in the Clay County jail in 1932 on a Prohibition act violation).

But by all accounts, he was not involved in the seamier side of the local outfit’s operations — murder, prostitution, etc.

“I have never done a thing wrong in my life outside a little gambling,” he told the Kefauver Senate committee that investigated organized crime in Kansas City and beyond in 1950 after the public and bloody murders of Binaggio and Gargotta.

His appearance at the Kefauver hearings turned Osadchey into a national figure almost overnight.

It’s possible that my father knew none of this notorious stuff when he was helping his friend in the early 1960s. But given that Dad was an avid reader of The Kansas City Star and Kansas City Times, which had detailed Osadchey’s testimony and mob connections, I suspect he had at least an inkling.

Of course, Dad wouldn’t have talked to us kids about his friend’s seedy past, just as he didn’t discuss his World War II experiences until decades later.

Most important to me was that Dad appeared to like Eddie Osadchey, and he didn’t like all that many people. But then, everybody seemed to like Eddie Osadchey.

Even federal officials at the Kefauver hearings.

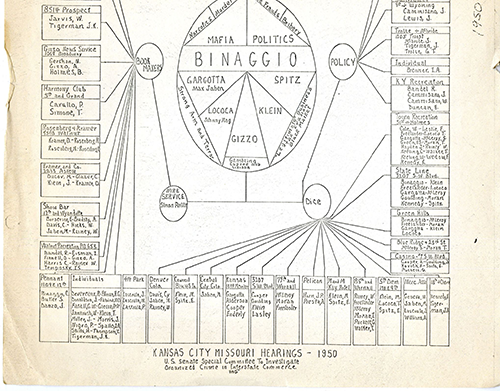

also known as the Kefauver Committee, showed the importance

Eddie Spitz (Eddie Osadchey) in the alleged Kansas City mob hierarchy.

Kansas City Public Library

Rudolph Halley, the committee’s chief counsel, advised Osadchey “to get a good lawyer and by a good one I mean one who is thinking of your interest and not trying to build up a fee in a criminal prosecution for you, an honest one.”

Sen. Charles Tobey of New Hampshire said: “You have got a bright mind and could go places in legitimate business. What intrigues you about crooked business that makes you go into it and bring in and embroil a good woman and a good son? … What is there in it for you? What is there in it, dear friend? Tell us, will you, please?”

Osadchey basically replied that he was just trying to make money and concluded, “I am out of the gambling business. I am through with it.”

No evidence suggests Osadchey broke that pledge.

The Civella connection

Before the Kefauver hearings, Osadchey’s name rarely appeared in The Star or any other newspapers. After them, the eyes of law enforcement were upon him. He was a marked man.

Federal tax liens totaling more than $50,000 were filed against Osadchey in 1952 for his activities of 1943 through 1945. He was prosecuted on a relatively minor federal charge in the late summer of 1964 for not paying taxes on liquor sold at Mirror Lake, eventually being sentenced to five years’ probation. The Star covered the case and the trial in some detail.

Seeing those stories for the first time now puts my father’s bookkeeping work for Osadchey in a new light. Was Dad somehow involved in something illegal? If so, it certainly would have been without his knowledge because he was the most honest man the world has ever known. If a store clerk had given him 10 cents too much change, he would have driven across town to return it.

So the real questions are when did he learn of Mirror Lake’s illegal scheme and what did he do at that point?

Perhaps it was just a coincidence, but the late summer of 1964 also was when my father abruptly decided to move our family out of the Northland and clear across town. Eddie Osadchey’s name never came up in our new house.

He did return to the national news in 1971, however, when Chiefs Hall of Famer Johnny Robinson — still an active player then — bought the Mirror Lake Town Club, signing a promissory note for $275,000 to be paid to Osadchey. That drew the interest of the NFL, and the Kansas City Crime Commission investigated.

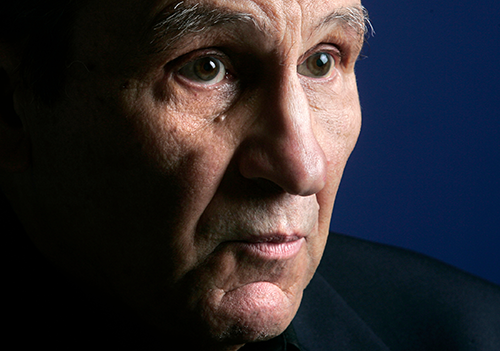

Frank Maudlin, the crime commission’s managing director, claimed that the then 64-year-old Osadchey’s association with organized crime figures was “a continuing sort of thing,” citing Civella’s arrest the previous October on a federal gambling indictment. Federal agents found him playing golf (with his wife) on the ninth hole of the Mirror Lake Country Club.

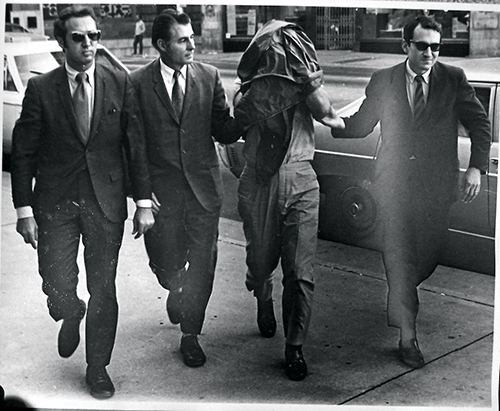

Kansas City crime boss Nick Civella, who hid his face from cameras. | File Photo

Civella previously had drawn attention to Osadchey and Mirror Lake in 1959, when the club was the venue of a party celebrating Civella’s 25th wedding anniversary. It drew hundreds of guests, including local politicians and alleged mobsters. Maudlin, a highway trooper at the time, wrote down the license plate numbers on 139 cars parked outside the club that night.

U.S. deputy marshals also had served Civella with a subpoena at the Mirror Lake Country Club in 1963 in connection with a gambling and racketeering investigation. On that occasion, Osadchey had greeted the marshals and denied that Civella was there, but when the officers left briefly and returned, they caught Osadchey and Civella chatting.

So he wasn’t the perfect role model.

The neighborhood

Eddie Osadchey also wasn’t our neighborhood’s only connection with alleged mobsters. It seemed as if half the families living in Sherwood Estates had Italian heritage, almost all of them upstanding citizens with kids who were among our best friends.

But a rumor spread that the father of a family less than a block away from us was a Mafia hit man.

That didn’t prevent my sister from walking to St. Gabriel with the daughters or my two brothers and me from playing almost daily games of backyard whiffle ball with the three sons. They always won. Always.

I also remember getting into a schoolboy fight with the youngest of those sons, and I’m pretty sure I was on the losing end of that, too.

In retrospect, that might have been just as well. Ouseley recognized the family’s name and confirmed the father’s reputation.

“He was a main figure in the organization and had the reputation of having done murders,” he said.

Ouseley helped arrest the man as part of the FBI’s Operation Strawman that investigated the skimming of $280,000 from the Tropicana Hotel in Las Vegas. A 1983 conviction resulted in a 20-year sentence.

The Mirror Lake clubs themselves had happier outcomes, although neither still exists.

The Town Club was purchased by a church in 1984 and has since operated as the Sherwood Bible Church and Sherwood Family Recreation Center. In 1973, Osadchey sold the Country Club, which became the Windbrook Golf Course. Some of the original Mirror Lake holes are now part The Deuce course at The National.

As for Eddie Osadchey, he died June 27, 1989, at the age of 83. His obituary described him as “a former golf and country club owner” who “lived in this area for 80 years.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.