Emery, Bird, Thayer met the wrecking ball. Did it save other Kansas City landmarks?

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

On Aug. 7, 1968, when the downtown Emery, Bird, Thayer department store closed for good, thousands of shoppers swarmed the huge building for a going-out-of-business sale.

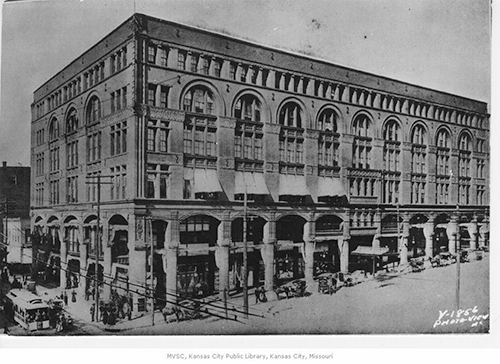

Forty-one police officers were assigned to control the crowd, the size of which perhaps challenged even the throng that had invaded the store on July 11, 1896. On that date, six years after the building was erected, an estimated 5,000 shoppers ascended to the third floor by 10 a.m. for a shirtwaist sale. Some 9,619 of the newfangled button-down women’s blouses were discounted from $1.25 to 25 cents.

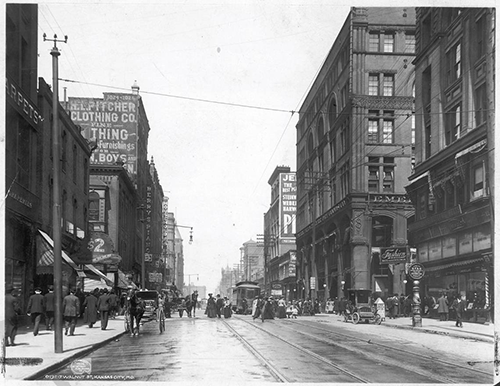

Called the “Big Store” in its early days — a 1915 story in The Star said there were “two acres of floor space” — EBT became a downtown institution and the king of Kansas City’s famous Petticoat Lane — a bustling block of 11th Street — during its nearly eight decades of operation. But with the emergence of malls and the resulting demise of retail shopping downtown, the end came on that hot summer day in 1968.

in 1901, some 11 years after construction. | Kansas City Public Library

The historic structure would stand empty for nearly five years, then would be demolished and replaced by a surface parking lot for another 10-plus years before a bank headquarters was finally constructed.

Like many Kansas Citians, reader Jane Murphy wondered why EBT met the wrecking ball instead of being preserved and repurposed. Her question to “What’s Your KCQ?,” The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ queries about our region:

Who was responsible for tearing down the beautiful Emery, Bird, Thayer and why did they?

Murphy was particularly befuddled because the structure had gained a place on the National Historic Registry just before being razed.

“I am puzzled and angry, and I have been for years, that that building was torn down,” the Overland Park resident said. “It was such a landmark building that it’s sickening that happened.”

that led to the demise of the downtown EBT building. | File photo by Keith Myers, The Kansas City Star

Reluctant villain

Every tragedy needs a good villain, and the demise of the downtown Emery, Bird, Thayer building had a made-to-order villain: R. Crosby Kemper Jr.

President of a bank, scion of an influential family (with an arena, foundation and art museum named after it), powerful force in the community. But Kemper, who died in 2014, was a reluctant villain at best and, as it turned out, a somewhat remorseful one as well.

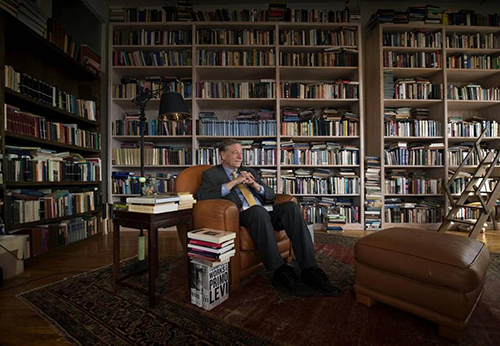

“It was a sore subject for him for a long time,” said his son, R. Crosby Kemper III, the longtime director of the Kansas City Public Library and now director for the Institute of Museum and Library Services in Washington, D.C.

Kemper Jr.’s City National Bank (later United Missouri Bank) obtained the EBT property shortly after the store closed. He told The Star in August 1972, “I bought the damn thing myself, and I didn’t sleep for nights. But the (bank) board saw the light and took it off my hands.”

His original idea was to bring in another business operation.

“He genuinely thought that it was a fine building, and he thought it could be a department store again,” his son said, indicating meetings with Marshall Field in Chicago and others proved fruitless.

At that point, Kemper Jr. decided to erect a headquarters building for City National Bank and hired the famous New York architect I.M. Pei to design it.

In the summer of 1972, as demolition began, he said he expected construction to commence in early 1973, telling The Star: “If anybody knows about a town, we ought to, and we’re putting our money where our mouth is, in the core of downtown. This town, what it really needs is pizzazz.”

Pei’s twin triangle-shaped office towers with 14 floors and glass facades certainly would have provided that. Instead, Kansas City got a big hole in the ground. When the final EBT brick was cleared in 1973, it left empty a full block along East 11th Street from Walnut to Grand.

“The Emery, Bird, Thayer building late last week was just like in the pictures of all those horribly bombed German cities,” Star columnist William D. Tammeus wrote.

The lot remained vacant until 1975, when Kemper Jr. announced he had abandoned the plans for a new headquarters and would build a surface parking lot. But it was a very nice parking lot, complete with a fountain, trees and objects salvaged from the EBT building.

Several letters to the editor in The Star savaged him. One read, “Thanks to a large bank, we now have the Kemper Memorial Parking Lot where once we had the Emery, Bird, Thayer Building.”

The parking lot was a downtown fixture — and a reminder of what had once stood there — until the mid-1980s, when Kemper Jr. returned to an old idea. In November 1986, United Missouri Bancshares’ $30 million, 250,000-square-foot headquarters — a six-floor building of pink, red and black granite — opened on the former site of the store.

Kemper III said his father believed the United Missouri building “made up for tearing down the Emery, Bird, Thayer building.”

“He genuinely felt he was a preservationist, so he was sorry he tore the building down. But I also think he felt a little guilty, and consequently some of what he did afterwards in terms of preservation was about the tearing down of the Emery, Bird, Thayer building.

“He was always trying to do the right thing. Did he always do it the right way? Probably not. He was very impulsive. He didn’t always plan well. But his heart was in the right place.”

director for the Institute of Museum and Library Services, said his father “was sorry

he tore the building down” and “felt a little guilty.” | File photo by Keith Myers, The Kansas City Star

Back to the Histoyr

Emery, Bird, Thayer manufactured memories that dated to the mid-19th century.

The business opened in 1846 as Coates and Bullene, then ran through several other name combinations before settling on Emery, Bird, Thayer. It occupied two other locations before the Big Store was built in 1890. The store got its name from investors William E. Emery, Joseph Taylor Bird Sr. and William B. Thayer.

A 1969 story in The Star about EBT’s history described “freshly scrubbed country boys and girls who wandered through the aisles, eyes wide with wonder of all the store held, as their mothers and fathers made annual purchases at Emery, Bird, Thayer.”

Customers enjoyed the wide aisles, latticed grillwork and other elegant touches, especially the brass elevator cages. They also were treated to personal service. The Star reported in 1915 that EBT had 2,000 employees. In 1968, 542 lost their jobs at the downtown store.

Murphy, whose question sparked this KCQ story, said one of her enduring memories is of the second-floor tea room that overlooked a mezzanine.

“It was such a treat, especially if you got a table right next to the overlook,” she said. “And I remember getting egg salad sandwiches all the time.”

That would have been years after legendary actress Joan Crawford, known as Billie Cassin at the time, worked there. As did Broadway star and Oscar-nominated actress Jeanne Eagels.

in about 1917. She worked briefly as a salesclerk at Emery, Bird, Thayer. | File photo

EBT’s history also included the racism that permeated the Jim Crow era.

Black people weren’t allowed to try on clothes or hats or to eat in restaurants until 1959. Also, a group called the Council for United Action accused the store of unfair hiring practices in 1968, claiming that of about 400 employees, only 24 were Black.

Eventually, EBT expanded to the Plaza and Independence. Macy’s bought those stores when Emery, Bird, Thayer went out of business in 1968.

In 1979, the EBT restaurant opened in the UMB building at Interstate 435 and State Line Road. It displayed artifacts from the old department store, including wrought iron archways and two of those brass elevator cages. The restaurant closed Dec. 31, 2015.

That leaves the EBT Lofts in the Crossroads District as the only surviving physical connection to Emery, Bird, Thayer. The six-story collection of one- and two-bedroom apartments is housed in a former EBT warehouse built in 1899.

‘Something important’ lost

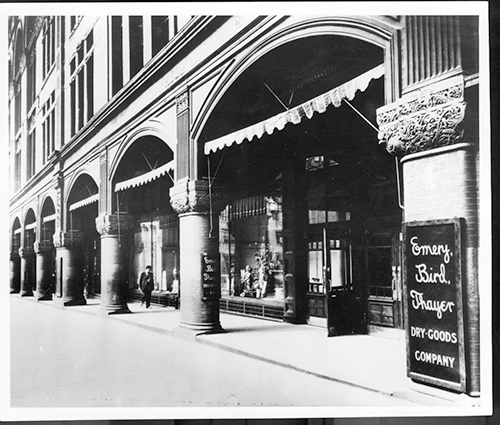

The Emery, Bird, Thayer building wasn’t merely a historical treasure, it also was an architectural jewel. An example of the free Romanesque style of the 1890s, it was one of downtown’s most important pieces of architecture.

Donald Hoffmann, The Star’s art and architecture critic, wrote: “When the wreckers pounded the building into dust in 1972 and 1973, many people realized that something important was being lost from the life of the city.”

Hoffmann described EBT’s exterior as “a husky, red, pressed-brick and sandstone, with carvings in the stone and other ornamental details in terra cotta.”

“But the arcades were the principal feature of the Emery, Bird, Thayer store — 450 feet of arched openings that skipped along Grand, turned the corner to hop down the 11th Street hill, then skidded around the corner again on Walnut.”

Hoffmann had provided support on the application to put the 1890 edifice designed by the Kansas City architectural firm of Van Brunt & Howe on the National Register of Historic Places:

“I think it could be stressed that, of the surviving buildings of Van Brunt’s, perhaps only Memorial Hall at Harvard (its tower unhappily truncated by fire) is more important than Emery, Bird and Thayer.”

So how could Kemper Jr. order it razed within months of its placement on the National Register?

Simple: Being on the National Register does not restrict an owner’s private property rights. No local regulations prevented EBT’s destruction either.

Cydney Millstein, a local preservation consultant and architectural historian who has worked on many nominations to the National Register of Historic Places, said she has been involved with a few other such National Register buildings that were torn down. Her relationship with Emery, Bird, Thayer is more personal.

“When I was kid, we lived east of Troost,” Millstein said. “And we used to take the streetcar downtown, with my mom, and we’d shop at Emery Bird. It was the department store when I was growing up.”

Millstein said not all old buildings are worth saving, but this one definitely was. In the 1960s and early 1970s, however, it was frequently a case of raze first and ask questions later.

“It’s a rather unfortunate period in our architectural history, I think,” she said. “It’s astounding what we lost from that period.”

But, she added, “back then, we had so few voices. That’s part of the problem.”

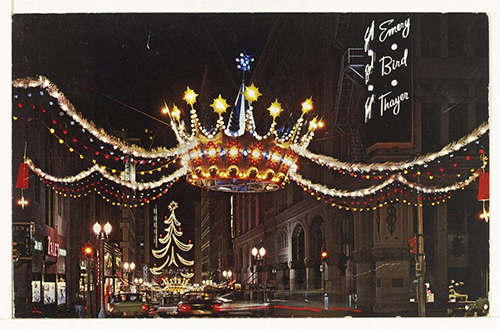

Both the downtown crowns and the store are long gone. | Kansas City Public Library

Attitudes changed in the mid- to late 1970s, and many people credited the demolition of Emery, Bird, Thayer for lighting the fire under local preservationists.

“The preservation movement in Kansas City belatedly trailed a national trend,” Hoffmann wrote in 1983, “and … the local impetus probably derived from the demolition of the old Kansas City Board of Trade Building and of the Emery, Bird, Thayer Store at 11th and Walnut Streets.”

It was no coincidence that the Historic Kansas City Foundation was founded in 1974. The Kansas City Landmark Commission (now the Historic Preservation Commission) had been established in 1970 but had little influence until a 1977 city ordinance added to its powers. It initiated the Kansas City Register of Historic Places shortly thereafter.

Joan Dillon, whose efforts in 1974 largely saved the Folly Theater from the wrecking ball, said she was inspired to act after the demolition of the Emery, Bird, Thayer building.

Kemper III even said that his father “liked to take credit for the modern preservation movement” because of the controversy his EBT decisions sparked.

Which raises the question: If the local movement had been stronger at the time, would the EBT building still stand?

Steve Nicely, The Star’s real estate editor, wrote in 1985:

“The memory of the magnificent Emery, Bird, Thayer department store building at 11th Street and Grand Avenue still haunts those who loved that giant antique. It has often been lamented that if only it could have survived another 10 years it would still be here today.”

Millstein said EBT’s street-level arcades would have been perfect for outdoor seating for restaurants, with apartments or office space on the floors above. Another suggestion was conversion into a mall-type arrangement filled with smaller shops.

Kemper III doubts that would have worked, pointing out that downtown was turning into a retail ghost town at the time.

“It took another 30 years to get retail in any way, shape or form back downtown,” he said. “And it’s not back downtown in a big way.

“If you hold it long enough, a lot of things could have happened to the site. But there’s a good building on the site, too.”

Good, maybe, but hardly in the class of what stood for more than three-quarters of a century.

“Emery, Bird, Thayer has such a rich history,” Millstein said. “Even if you didn’t like the architecture, chances are you loved the store.

“It was a shopping experience, and there are no shopping experiences today. I dread going shopping.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.