Due to flooding Mobile Services is canceling all Books to Go deliveries and all afternoon Bookmobile stops for the week of Monday, July 21st.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Jeremy Drouin

This spring has been like no other as social distancing and quarantining, at least for the time being, have replaced community events and gatherings.

A leisurely neighborhood stroll or scenic drive, while keeping a safe distance from others, can help relieve the stress of cabin fever. A city parkway that is perhaps unknown to many residents is Cliff Drive, the focus of this week’s installment of What’s your KCQ?, a community reference partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Star.

We look back at one of the city’s earliest recreational roadways, responding to a question from reader Dee Wallace about its origin and intended use.

Cliff Drive was part of noted landscape architect George E. Kessler’s original plan for Kansas City’s parks and boulevards system. He designed it to wind through the wooded hills and along the limestone bluffs of North Terrace Park, renamed Kessler Park in 1971 to honor his vision.

Now known as the Cliff Drive State Scenic Byway, the nearly four-mile road stretches from The Paseo and Lexington Avenue east to Belmont Avenue, through the historic Northeast’s Pendleton Heights, Scarritt Renaissance, and Indian Mound neighborhoods.

From “Squirrel Pasture” to Park

In the early 1890s, Kessler was commissioned by the newly formed parks and boulevards board to transform some of the city’s blighted areas into green space. His vision, influenced by the emerging City Beautiful Movement, was a network of parks connected by scenic boulevards that accentuated rather than ignored the city’s rugged landscape and other natural features.

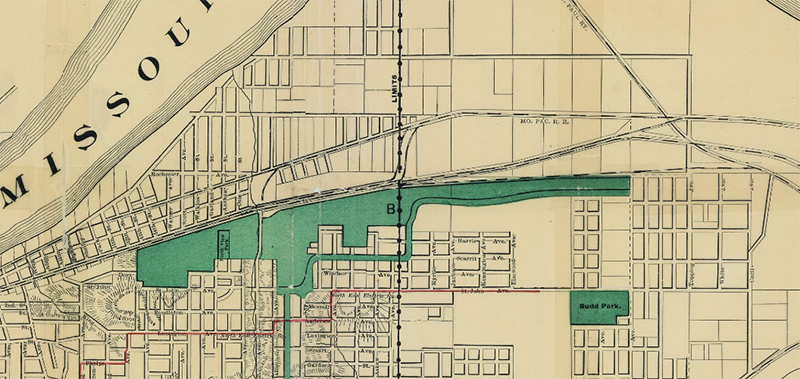

Kessler’s proposed park system in 1893 included the development of what he then called North View Park along the bluffs overlooking the East Bottoms and the Missouri River. The area was originally homesteaded by the Rev. Nathan Scarritt, a Methodist minister who had moved his family from Westport in 1862 to escape Civil War hostilities. He prospered as a farmer and continued to purchase property northeast of Kansas City.

In the mid-1890s, the park commission began acquiring land along the bluffs for the development of North Terrace Park – much of it deeded by the Scarritt family. But the proposed park site was not without its detractors. Critics proclaimed it a “squirrel pasture” and “too rugged for a goat to climb,” and property owners challenged the city’s authority to secure park land through condemnation. The Missouri Supreme Court ultimately upheld the acquisition, and construction of North Terrace Park began in 1899.

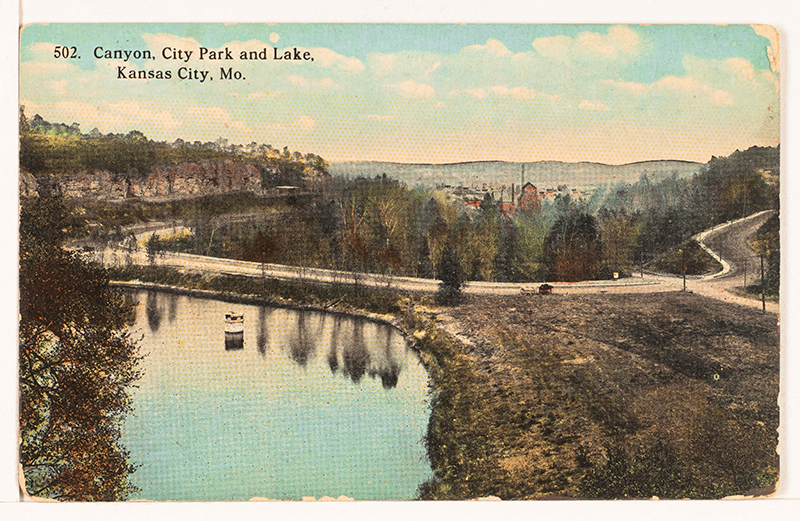

Cliff Drive was to be the signature feature. It would not only provide for optimal viewing of the surrounding scenery, but also connect the east and west park regions separated by a large ravine.

Grading of the eastern section of road was completed in 1900. Five years later, west Cliff Drive was opened to the public, bringing the total length to just over three miles. A grand opening was held July 30, 1905. The Kansas City Star called it “one of the most picturesque driveways in connection with any municipal party and boulevard system in America” and “three miles of as perfect roadway as can be made.”

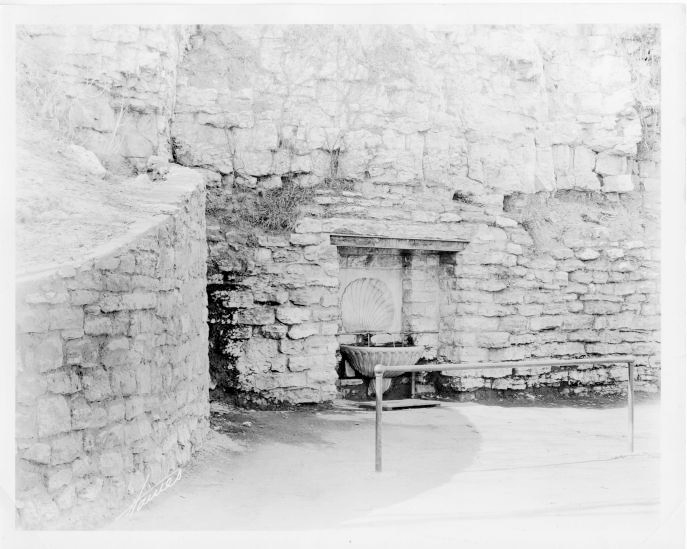

Kessler continued to make improvements. Retaining walls were built to stabilize the bluffs, and a drainage system was installed for storm water runoff. In 1906, a natural spring near the east entrance was converted to a public drinking fountain, providing refreshment to thousands of thirsty park goers annually. In 1907, gas lights were installed every 100 feet to illuminate the route at night.

Traffic Jam

Cliff Drive’s winding path through the wilds and along the bluffs was designed for leisurely walks and carriage rides. However, the emergence of a new mode of transportation, the automobile, presented a problem for park officials and pedestrians.

Early motorcars were noisy, unreliable, and unwieldy to drive – a dangerous combination when navigating tricky curves and steep cliffs alongside skittish horses pulling passengers. Kessler saw the potential conflict of motorists sharing the roadway with pedestrians and carriages, and hoped to eventually construct a network of bridle paths to give riders and walkers better access to the park “in security from the automobile speed-maniacs.”

The park board approved a resolution in 1903 prohibiting motorized vehicles on Cliff Drive. The ban was precipitated by an incident earlier that year, when occupants were thrown from a carriage after a passing automobile startled the horse pulling it. It was noted in a report by the park superintendent that the passengers barely escaped tumbling down a cliff, and the driver journeyed on “giving no thought to danger in which the persons in the carriage were placed.”

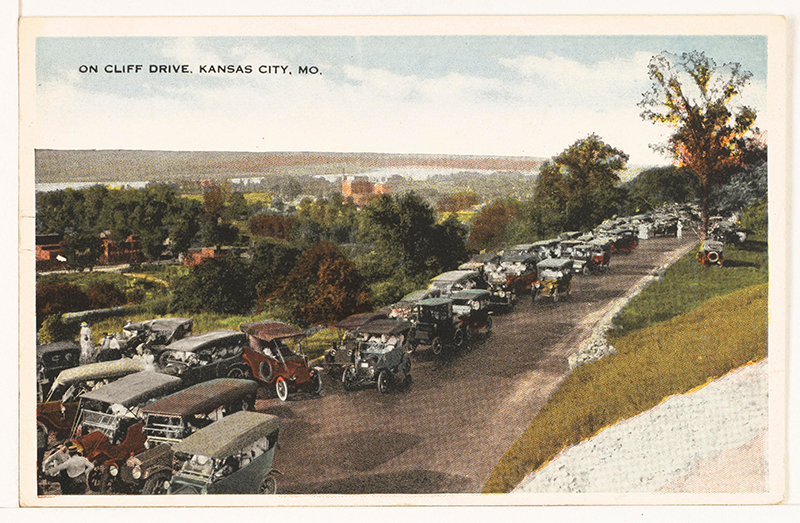

The motorcar ban was short-lived, however. The Kansas City Automobile Club successfully pressured park commissioners for access to Cliff Drive and later lobbied against an effort to disallow motorized vehicles on Sundays. The rising popularity of automobile travel proved too much to keep motorists off the city’s most picturesque thoroughfare. Instead, the focus was making Cliff Drive safer for drivers.

By the mid-1920s, the temperamental gas lamps along the route were replaced with brighter and more reliable electric lighting. This made for safer nighttime driving and discouraged would-be robbers. The most dangerous curves were rounded to make them easier to navigate, and paving began on stretches of the roadway.

Additionally, stone barricades were constructed along north sections of the drive as a security measure for motorists. Several pull-offs were also added so sightseers could stop and take in the best views of the Missouri River valley below.

By the spring of 1927, Cliff Drive had been widened sufficiently to allow two-way traffic. For many years, the drive was designated one-way westbound for automobiles, forcing motorists to enter the east terminus at Gladstone Boulevard and Elmwood Avenue. Today, it is the eastbound lane that is open to vehicle traffic (Monday-Wednesday) while the westbound lane is designated for bicyclists and pedestrians only.

Cliff Drive’s Legacy

In the decades after its completion, Cliff Drive stood as one of George Kessler’s greatest achievements and a popular destination for residents and out-of-town visitors alike. The drive was advertised as a signature tourist attraction of Kansas City, alongside such destinations as the Liberty Memorial, Union Station, and Country Club Plaza. By the end of the century, however, the route was plagued by deteriorating roads and rampant illegal dumping. A landslide in 1998 closed the roadway.

In an effort to restore Cliff Drive to its former glory, the Kansas City Parks and Recreation Department and former state representative Ronnie DePasco successfully campaigned to make it a state scenic byway in 2000.

State funds helped provide for much-needed roadway repairs and trash cleanup. And on October 11, 2001, a ribbon-cutting ceremony celebrated the reopening of Cliff Drive. Additional work was completed in 2015 to restore aging staircases, overlooks, and stone walls. Kiosks were also installed at the Paseo Gateway and Kansas City Museum entrances to inform the public of the drive’s historical significance and identify points of interest along the route.

For information about Cliff Drive’s access points and restrictions, visit the Kansas City Parks and Recreation website.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.