How Admiral Avenue Got a Promotion – to Admiral Boulevard

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Matt Reeves | lhistory@kclibrary.org

As Kansas City was growing up in the late 19th century, its leaders recognized the need for respite from the hubbub of urban life. They set aside green spaces, the parks that would become an identifying feature of the city, and built wide, inviting boulevards to connect them.

A “What’s Your KCQ?” reader points to one of those important connectors, asking, “When was Admiral Boulevard designed and built?” And beyond that, “What was the goal of the parks and boulevard(s) system?”

Admiral Boulevard once was just an avenue, a route between the early downtown business core and available housing to the east. Its upgrade to a boulevard 120 years ago this month illustrated the struggle planners faced in creating a vibrant city, sometimes at a high cost to some of Kansas City’s most vulnerable residents.

The intersections of infrastructure, power, and structural racism are prominent topics. And the history of our parks, boulevards, and highways demonstrates such projects, masked with the intention to create beauty, also enacted disproportionate harm to low-income communities and communities of color.

The Town of Kansas booms

By the 1890s, Kansas City was an overcrowded mass of tenements, businesses and factories. Narrow streets and endless blocks of buildings left little to no green space. The town had grown at an incredible rate in the decades after the Civil War. With an assist from the new Hannibal Bridge over the Missouri River in 1869, it was now a vital link between timber and livestock producers in the West and hungry urban markets back East.

As businesses grew, so did the populations that worked in slaughterhouses, railyards, and factories. By 1890, more than 132,000 people lived in the metropolis that was appropriately rebranded as Kansas City.

Most 19th century cities had a bad rap, and Kansas City was no exception. Unimaginable growth intersected with the absence of effective municipal planning. There was a lack of space for recreation, and roads, designed when the city was smaller, were often narrow arteries that invited congestion. Many were unpaved, unlit and generally unfit for bustling traffic.

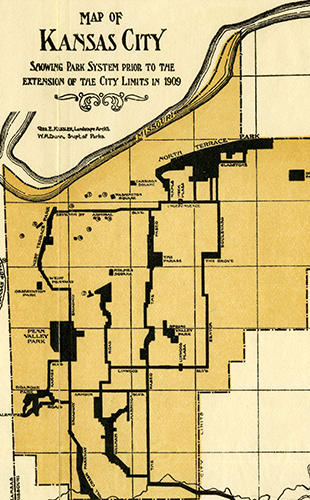

Sensing an opportunity to improve the city’s function and image, Mayor Benjamin Holmes established the Office of Park and Boulevard Commissioners in 1892. Under the leadership of August R. Meyer, it started an ambitious effort to build a system of parks and boulevards throughout the city.

Kansas City’s parks board was part of a broader international movement to beautify urban areas and support arts and culture. The board’s first report acknowledges a debt to Frederick Olmstead, the eminent landscape architect who had built America’s most famous urban green space, Central Park, in the 1850s.

The aim in Kansas City was to provide similar breathing room. For businessmen, the initial report said, parks would “invite rest and contemplation and the dropping of all business cares.” Green spaces freed children from “the mind and body destroying influences of crowded tenement houses.”

The board further argued that all Kansas Citians needed “the quiet, healing, and recreative influence of pure, unalloyed nature to reestablish and maintain the moral and physical equilibrium.” Cities could make you ill, and well-designed parks were good medicine.

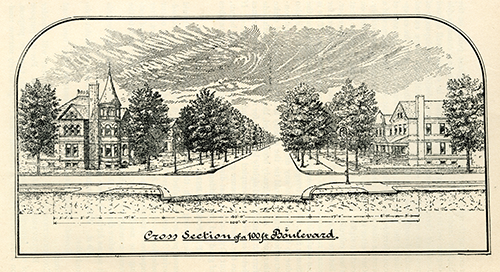

Boulevards were the essential networks for travel from park to park. As the commissioners said, they “should more properly be called parkways,” or parks designed for moving. Boulevards were nearly twice as wide as regular roads, paved with macadam (an early pseudo asphalt), and designed for both regular transit and leisurely rides.

Areas cleared using eminent domain

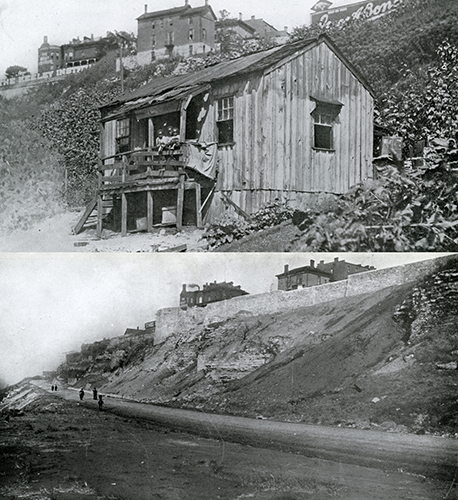

George Kessler, who was inspired by Olmstead’s design principles, became the leading figure of Kansas City’s parks and boulevards movement. Seizing the moment and the land, the city cleared areas using eminent domain.

Much like in New York, the acquired land did not include spaces where prominent structures already existed but, instead, places where working-class Kansas Citians had built improvised communities using whatever materials were at hand.

For Kessler and the parks board, the movement was an opportunity to add to civic beauty while simultaneously removing what they saw as eyesores blighting the landscape. Property in Quality Hill and homes of prominent Kansas Citians in the Northeast went untouched.

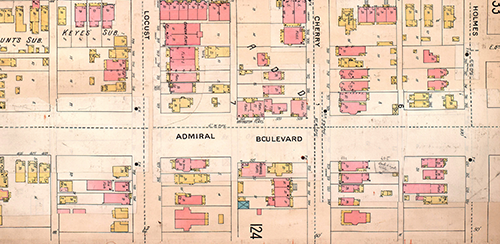

While other elements of the City Beautiful movement were about beautification, Admiral Boulevard was also about transportation. The broad, 100-foot roadways opened an efficient path from the downtown business core to the Northeast. A Star reporter wrote in 1898 that “no more desirable improvement has been proposed in Kansas City … than Admiral Boulevard.”

The reasons were many. It would create more demand for housing in the north end, better driveways to the East side, and “a beautiful boulevard at a remarkably light expense without any injury to any interest which the public is under obligation to regard.”

That begged the question: What injuries, and whose, would be regarded?

The parks and boulevards system gave Kansas City gorgeous municipal infrastructure, but it also established a precedent for urban renewal that placed the right of eminent domain over the rights of blue-collar Kansas Citians. Projects often targeted low-income areas for razing and replacement.

The pattern of displacement and construction continued in the years after World War II. Hungry highway systems bisected communities and swallowed up Black and Latino neighborhoods in the 1960s. As in other places across America, those redevelopments generally put the needs of wealthier, white Kansas Citians first.

The parks board passed a resolution authorizing Admiral Boulevard on Nov. 21, 1900. Transforming the avenue meant widening, regrading, and paving the road and installing retaining walls. Costs were assessed to property owners along the boulevard, leading to some pushback. But ultimately, the prestige of living on a prominent roadway was worth the expense — for some.

The disruption of working-class communities and communities of color had a history tracing to Olmstead and Central Park. New York City used eminent domain to claim the center of Manhattan Island, then razed buildings and displaced the communities that lived on that property. Seneca Village, a predominantly Black community, was among the settlements seized and destroyed to make way for the park.

The popularity of Central Park inspired the City Beautiful movement, which spread across the nation and gained steam in the boom years after the Civil War. Kansas City’s campaign created lush green spaces but also exposed whose rights were deemed disposable.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.