All Library locations will be closed Wednesday, December 24 and Thursday, December 25, for Christmas.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Randy Mason | Kansas City Star

Sometimes, “What’s Your KCQ?” gets more than one question on the same topic. That’s the case this week.

A reader asked how “a small Black neighborhood…sandwiched between Westport and the Country Club Plaza” could have flourished in the days when restrictive covenants excluded people of color from owning homes in certain areas.

Another referred to the neighborhood by name—Steptoe—and wanted to know more about its history.

Let’s start with the second question, which may help answer the first.

How did the Steptoe neighborhood come to be?

The area that came to be called Steptoe officially began life in August 1857. It was called Pate’s Addition to the Town of Westport, named after Henry Clay Pate. He was a Virginia native, and a prominent figure in the pro-slavery movement.

Yes, you read that right.

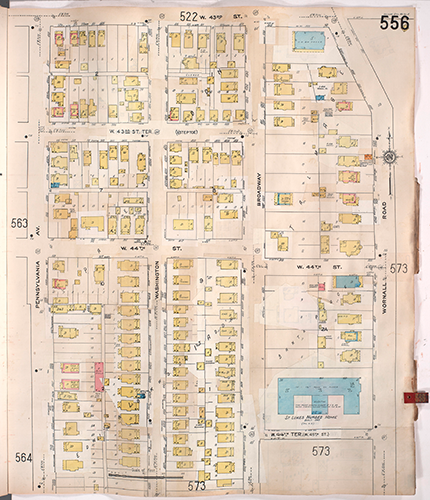

A pasture at the time, Pate’s Addition ran from what is now W. 43 Street south to W. 44 Street, and from Wornall Road to Summit Street.

Aerial photo of the area where to Steptoe neighborhood was, today. | Todd Feeback

For recognizable reference points, think St. Luke’s Hospital at one end, with the venerable Temple Slug at the other. Much of the rest is parking lots, apartment complexes and medical buildings.

Who was this Pate character?

Pate was a white soldier. In 1856, he was captured by John Brown’s forces at the Battle of Black Jack near Baldwin City, Kansas.

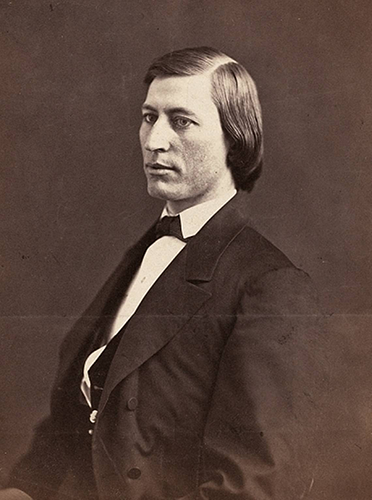

Henry Clay Pate portrait | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Daniel Smith, a former President of the Civil War Roundtable, has been researching Steptoe for the Westport Historical Society. He noted that prior to the Civil War, land speculation along the Santa Fe Trail ran rampant, which would have made the land that became Steptoe a hot commodity.

Since Pate wasn’t particularly wealthy, Smith believes some of the funds for his development came from well-heeled family friends back in Virginia.

The family friends were named—you guessed it—Steptoe. That explains why Steptoe Street (W. 43 Terrace since 1933) ran through the heart of Pate’s Addition.

But Pate wasn’t around long enough to prosper from his investments. He returned to Virginia, joined the Confederate Army and was killed in battle in 1864.

Wait—wasn’t Steptoe a safe haven for Black families to thrive?

Yes, but not right away.

Stories told about the origins of Steptoe often suggest the land was somehow set aside for formerly enslaved people and populated by “Exodusters,” or freed Black people who headed West for new opportunities.

But evidence to support that is scant.

In fact, Smith says, the platted land saw little activity in the first few years after the Civil War, other than Pate’s debtors claiming some of the lots for themselves.

Those debtors in turn may have sold land to the handful of Black farmers that began to appear in the Kansas City census in 1870 and 1880, which is how the area started to become more integrated.

Black farming families with names like Collins, Hamilton, Hudson, Maupin and Edgington, owned properties clustered together around Steptoe Street, in a setting that remained rural for quite some time.

As in other corners of Westport, records show these Black residents always had white neighbors. Ethnically diverse, some came from as far away as Ireland, Germany, Prussia, and the case of a sheep farmer named Sam Ellis—London.

The first school for Black children West of the Mississippi

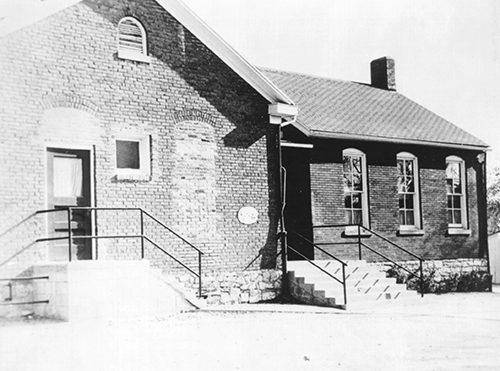

Ellis played an interesting role in Steptoe’s growth. In 1868, his young wife, Marian was hired as the first teacher at the newly opened Penn School.

The three-room brick structure at 4237 Pennsylvania—near where the Embassy Suites Hotel stands today—was the first school west of the Mississippi River built exclusively for Black students.

Penn School, 4237 Pennsylvania, (built 1868) | Kansas City Public Library

Missouri’s constitution prohibited Black students from attending class with white students.

For nearly 90 years, Penn School housed grades 1 through 7 in that location. Through its doors came future business leaders, teachers, politicians and one superstar musician—Charlie Parker.

In the biography, “Bird,” Chuck Haddix reveals that Parker picked up his first saxophone in the 5th grade, thanks to a Penn School music program. It’s also where he picked up the nickname “Yardbird” for misbehaving at a school costume pageant!

By the time Parker was attending Penn School in 1927, the area around it could no longer be called agricultural.

Penn School students 1931 (Charlie Parker second from left, top row) | LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC

“A relatively unsegregated working-class community”

Kansas City annexed, or absorbed, Westport into the city in 1897, as more and more Black people migrated into the metro area. The influx came largely from other towns in Missouri and southern states like Kentucky and Tennessee.

Steptoe reflected that trend of Black migration. The 1900 census reported that the 4th Ward, home to both of Pate’s Additions, now contained 220 people, and 34% of them were Black.

Rather than a completely “Black enclave,” Smith says those stats describe a “relatively unsegregated working-class community”—one whose residents were primarily employed in manual and domestic labor.

In the early 1900s, the numbers of Black families continued to climb. Streetcar lines made it possible to live further from the workplace, whether it was railyards, a plumbing shop or the home of an affluent family that needed childcare.

Instead of farmhouses, modest homes and apartments built in Craftsman and Folk Victorian styles kept popping up along Steptoe, or W. 43 and W. 44 Streets.

Kansas City’s Steptoe neighborhood, between Westport and the Plaza. | Kansas City Public Library

An island, a village, a treasure

The timing of that small construction boom—1895 to 1910—proved to be incredibly important, Smith believes, because it meant Black families owned homes.

Soon, the rise of restrictive real estate covenants enacted by white officials would leave Black and brown homebuyers with even fewer options.

Steptoe’s attractive housing stock and the reassuring presence of Penn School were key factors in helping “the hill” add new residents in the early 20th Century.

Another was its churches.

Both were built on 43 Street. The Saint Luke’s AME Church (razed in 2003) and the St. James Missionary Baptist Church (still standing) first opened their doors in 1879 and 1883 respectively.

Saint Luke’s AME Church, W. 43 St. and Roanoke | Kansas City Public Library

They’d long served as spiritual and social centers for a Black community that found itself integrated in some ways and shunned in others.

Steptoe in its heyday is often described as an “island” or a “village.” In a 1997 article in the Kansas City Star, longtime resident Mary Louise Hinton called it a “treasure” and said she felt “insulated” growing up there.

Basil Philips told the same reporter, “It was the kind of place where you hand-delivered Christmas cards.”

A good thing came to an end

But life there wasn’t always so harmonious.

In her local history column for the Martin City Telegraph, Diane Euston looked back at a proposal the city’s Park Board received in 1921: A group of “Westport property owners” wanted homes along Steptoe Street from Washington to Broadway condemned to make way for “a public playground.”

The Star reported that Black residents and some of their white neighbors objected strenuously. The board concurred, ruling that “the majority of property owners in the district opposed the project.”

Courtesy of Kansas City Public Library

Steptoe’s eventual demise was far less dramatic. Penn School closed in 1955 as the city made plans for desegregation. Gradually, St. Luke’s (where many neighborhood residents had worked in laundry or maintenance capacities) bought up more and more of the well-worn homes, replacing them with parking garages, surface lots and space for future expansion.

Today, only seven houses remain—lined up on the south side of 43 Street.

“A Step Above the Plaza”

No story of Steptoe is complete without mentioning Joe Louis Mattox, a historian who wrote extensively about the area. Shortly before his death in 2017, Mattox teamed with Rodney Thompson on an oral history video called “A Step Above the Plaza.”

The voices in it speak lovingly of the streets and schools, the people they knew, and the life lessons learned there.

These days, that’s about all that remains of Steptoe.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.