All Library locations will be closed Wednesday, December 24 and Thursday, December 25, for Christmas.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Randy Mason | Kansas City Star

Quindaro only lasted for six years—but one hundred sixty years later, it still fascinates people for its links to the Underground Railroad.

The Kansas town sprang up on the south banks of the Missouri River between Leavenworth and Kansas City in early 1857, a time when the Kansas-Nebraska Act spurred “free soilers” and pro-slavery forces to battle over the future of the state.

Many of Quindaro’s founders were Northerners affiliated with the New England Emigrant Aid Society, an abolitionist group that settled Lawrence a few years earlier.

They chose a site to create the town six miles above the mouth of the Kansas River, on the northern edge of what is now Kansas City, Kansas.

A rock ledge at the foot of its steep bluffs and wooded hills created a natural landing for steamboats. The town founders made it the only port on that stretch of the Missouri not controlled by Southern sympathizers.

They purchased the parcel from the Wyandot tribe, which settled there in 1843 after the U.S. government forced them to move from Ohio.

The new town took its name from a tribal member, Nancy Quindaro Brown Guthrie. Her husband, Abelard Guthrie, worked with the Wyandot in Ohio, and helped the Town of Quindaro Company broker the deal.

Keeping Kansas free from slavery was an important part of the founders’ mission, but they also profited from the deal. Border wars or not, land speculators demanded a substantial return on their frontier investments.

A THRIVING TOWN

The speed with which Quindaro took shape was nothing short of amazing.

By summer of 1857, the new town had 600 residents, two hotels, a sawmill, a brickyard, a grocery store, hardware store, doctors, lawyers and despite the presence of a strong temperance movement, a tavern or two.

The muddy streets were cleared and graded for easier access to the commerce that clustered around Kanzas Avenue, stretching uphill toward what is now N. 27th Street.

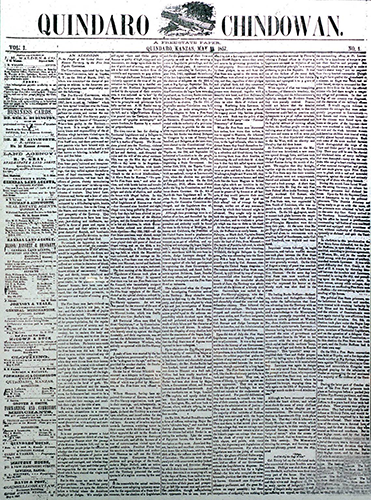

Quindaro had its own newspaper, the Chindowan—a Wyandot word meaning “leader” that was filled with civic boosterism and free-state advocacy.

Clarina Nichols was co-editor of the Chindowan. A widow from New England, she later made headlines of her own in pursuit of women’s rights and suffrage.

A STOP ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

In 1882, a memoir Nichols wrote for the Wyandotte Gazette pulled back the veil on Quindaro’s role in the fight against slavery. She revealed that “conductors” on the Underground Railroad often used a house nicknamed “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” for harboring runaways. Most notably, she claimed to have sheltered a young girl in her own cistern.

“One beautiful evening in October ‘61, as twilight was fading from the bluff,” she wrote, “a hurried message came to me from our neighbor, Fielding Johnson: ‘You must hide Caroline. Fourteen slave hunters are camped in the Parkhe, r master among them.’”

Another Quindaro resident, Benjamin Mudge, wrote a letter in February 1862 published later by the Kansas State Historical Society including a tale of slave hunters at his door looking for “contraband” that they (correctly) believed Mudge was hiding.

Bluffing that he was “heavily armed,” Mudge proclaimed, “I don’t want to harm anyone, But if any man enters my house in the night… he will likely get hurt.” The men outside threatened “to go see the captain,” but didn’t return.

It was too risky for those harboring formerly enslaved people to keep close records. But area families often passed down stories of ancestors who fled to freedom in Quindaro, sometimes by slipping onto the ferry that connected it to Parkville.

One person named Doc Harris told his family his story of literally walking across the ice-covered river with a small band of enslaved people. His great-great-great grandson Herbert Harris shared the family lore for an oral history project.

Many of the formerly enslaved eventually found their way West to Lawrence, Leavenworth, or other “stations” on the Lane Trail that led north to safe havens in Nebraska and Iowa.

A BOOM TOWN ABOUT TO GO BUST

But some of the freedom seekers who came to Quindaro decided to stay—in a boom town that was about to go bust. In 1858, the population reached 1,200, just as a tidal wave of setbacks washed over it including a financial panic.

Vacant homes and businesses—and squabbles between the town’s founders —soon followed. In 1862, the new State of Kansas revoked the Town of Quindaro’s charter.

To make matters worse, the Union army used some of the empty structures to house troops during the winter of 1862, leaving damage and debris in their wake.

While the commercial core near the river shut down entirely, some of the homes further up Quindaro’s rugged bluffs remained in use.

UP THE HILL, QUINDARO REMAINED

In the years after the Civil War, the African-American population at the top of the hill and west along Happy Hollow Road continued to grow.

Rev. Stacy Evans, pastor of the Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church believes that Black people who’d left states in the South were drawn by employment opportunities in Kansas City’s packing houses and railroad yards.

Education also played an important part in drawing people to Quindaro.

In 1862, Eben Blachley, a Presbyterian minister, started a school there for Black children. After the war, he continued teaching at what became the Quindaro Freedman’s School.

With assistance from the State of Kansas, the town added a teacher training school in 1873. Charles Henry Langston, grandfather of the poet Langston Hughes, served as its first president.

THE WEST’S FIRST BLACK COLLEGE

Beset by financial problems, the school struggled. In 1881, the A.M.E. Church reopened it as Western University, the first all-black college west of the Mississippi.

Ten years later, Western moved up from the valley to a hilltop location at 29th St. and Sewell Avenue.

Ward Hall was the first of six brick buildings that marked the campus. The school’s curriculum included industrial training, printing, dressmaking, business classes and most notably, music studies.

Western’s Jackson Jubilee Singers were a national attraction in the early 20th Century.

In 1911, the school dedicated a marble statue of John Brown holding the Emancipation Proclamation. it served as a reminder that, even if he’d never been there, Brown’s cause of freedom and Quindaro’s legacy as a town that helped people get to freedom would always be intertwined.

Dwindling enrollments, the Great Depression and WWII finally forced Western to close its doors in 1944.

PRESERVING QUINDARO

For the next 40 years, Quindaro quietly held onto its heritage despite little recognition beyond the neighborhood’s borders.

Then in the mid-1980s, trash put it back in the headlines. Browning-Ferris Industries proposed to build a landfill on the old Quindaro townsite. Residents, historians and preservationists rallied to stop the project—and succeeded.

on Monday, May 9, 2005, at the Quindaro ruins in Kansas City, Kan. The men were working on the Otis

Webb building. In the background are the foundations of the Jacob Henry building and the Wyandott House hotel.

Once clean, the joints will be tuckpointed.

Archaeological teams uncovered the ruins of 22 buildings from Quindaro’s boom town past—the largest of them a brewery. Thousands of artifacts from the overgrown site were sent to the State Historical Society in Topeka.

in Kansas City, Kan. The brewhouse will be cleared of debris and foundation stones will be re-layed

during upcoming restoration work. Collins is framed by the opening leading

into the structure’s barrow-shaped storeroom. | Kansas City Star

Today, a scenic overlook at 27th and Sewell is still the most visible reminder of Quindaro’s historic past. Down the street, an Underground Railroad Museum operates in the Vernon Community Center. Around the corner, the Old Quindaro Museum holds its own collection of artifacts and mementos.

In 2019, Congress proclaimed the townsite a National Commemorative Site. Proponents like Marvin Robinson, who told the Kansas City Star the ruins are “the Pompei of Kansas,” continue to push for designating it as a National Historic Landmark. With a state-of-the-art interpretive center.

They know it won’t be cheap.

Because the A.M.E. church owns most of the land, Rev. Evans says she’s been “laser focused” on ways to make the area more visitor-friendly. Starting with the trails that run downhill from the overlook.

They’re currently closed. She calls them “daunting.”

But there is some movement. Evans says an agreement has been signed with the Unified Government of Wyandotte County and KCK, which also owns a few of the tracts.

ruins overlook on Wednesday, June 25, 2008, at the north end of N. 27th Street in Kansas City, Kan.

The Missouri River can be seen off in the distance. | Kansas City Star

That means work could begin as soon as spring on the first phase of a project to cut back the overgrowth, clean the trails and start stabilizing the ruins.

Though it isn’t found in her job description, Evans admits that the quest to honor those who built and sustained Quindaro has truly become a passion.

“It’s a great story,” she said simply. “And it needs to be told.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.