Shawnee Indian Mission wasn’t always in Johnson County. KCQ finds the forgotten story

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Dan Kelly

The Rev. Thomas Johnson is a central figure in the history of Kansas, especially in the county that bears his name.

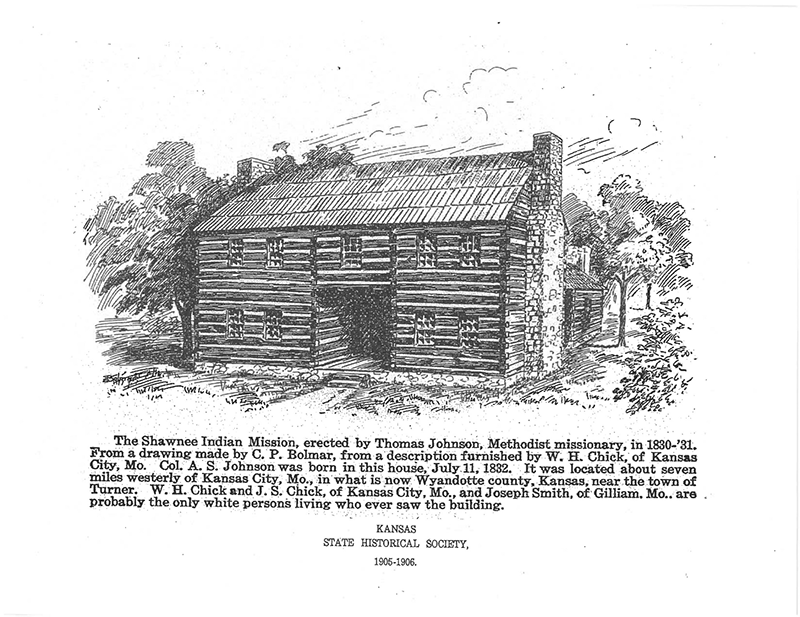

But in 1830, when Johnson settled in what would become Kansas, he put down roots in the Turner area of what is now Wyandotte County, where he established the Shawnee Methodist Mission.

Johnson later moved his mission several miles to the southeast. The surviving buildings in Fairway now make up the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site, a National Historic Landmark.

So, what happened to that original site?

Reader Zoann Merryfield raised that issue with her question to “What’s your KCQ?”: “Is there a monument to the first Indian Mission in Turner, KS? Predecessor of the still extant Shawnee Indian Mission.”

“What’s Your KCQ?” is an ongoing series in which The Star and the Kansas City Public Library partner to answer readers’ queries about our region. We usually find most of our background in The Star’s archives, and the library provides information and photos from its files.

In this case, The Star’s files were of little help. It has written virtually nothing about the monument in question and very little about the original Shawnee Methodist Mission.

But The Star isn’t alone. It’s safe to say the Wyandotte County site has been the forgotten stepsister in the Shawnee Mission saga, despite its historical significance.

The U.S. government moved the Shawnee Indians from Missouri, Ohio and Eastern states to the wild lands to the west in the late 1820s. Johnson, a member of the Missouri conference of the Methodist church, followed the Shawnee to the area.

The Baptist and Quaker churches also operated missions for the displaced tribes, but Johnson’s Methodist mission was the most ambitious as well as the most controversial. The mission and its manual labor school not only sought to “civilize” Indians and convert them to Christianity, they also generated considerable revenue for the Methodists and for Johnson, a slave owner who eventually was murdered in Missouri.

In any case, its place of origin has been virtually lost to history — twice.

It likely still would be lost if not for the efforts more than 100 years ago of E.F. Heisler, the editor of the Kansas City Sun in Kansas City, Kansas. Heisler was a crusader for the Turner mission both in deed and in print.

By the late 19th century, it was as if the mission’s original site never existed. Having been converted into a private residence after the 1839 move to Fairway, the building fell into decay and evidently was removed.

Heisler spent years researching the topic and found no record of the original mission at the Kansas Historical Society or in seven histories of Kansas. Ultimately, he confirmed the existence of the two-story log mission through conversations with old-timers, including Alexander Soule Johnson, who was born there. Alexander Soule Johnson, the son of Rev. Thomas Johnson, is considered the first non-Native American born in Kansas.

Heisler, with the help of an elderly Native American woman who had visited the place, found the building’s foundation in 1912.

R. Hendrix during the 1917 the dedication. | kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society

It took another five years for him to persuade the Kansas Methodist Historical Society to erect a monument on the original site. His newspaper covered the June 26, 1917, dedication ceremony with a full page of stories and photos, and several pictures of that event survive at the Kansas Historical Society. Among those attending were Julia Stinson, a Shawnee descendant born in 1834 a half-mile east of the site, and 5-year-old Sue Wornall, the great-great-granddaughter of mission founder Thomas Johnson.

Unfortunately, the granite marker, which stood 5 feet tall and included a 10--by-18-inch bronze plaque, eventually went the way of the original mission.

On June 4, 1950, The Star, in its only story mentioning the monument, said, “The granite marker is now hidden in a peach orchard about three-quarters of a mile southeast of Turner.”

Fast-forward about 60 years, and that peach orchard in the 5100 block of Edgehill Drive had been developed with residences.

Enter John Forbes, retired history teacher and librarian for the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site. He followed in Heisler’s footsteps and undertook the task of finding the 1917 Turner monument.

“You had to peer between houses to see it,” he said. “The area was overgrown, and the monument had been vandalized. We took it to the Mission. The decision was made that it made more sense to be here than there.”

To be precise, only the bronze plaque portion of the 1917 monument made the trip to the Fairway museum about 10 years ago. It is not on public display, but Forbes said anyone who wants to see it can call ahead and arrange for a showing — but only on Wednesdays, his day in the office. And only when the museum reopens; it’s closed until further notice because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The story doesn’t end there, however.

Around the corner from the site of the 1917 monument in Wyandotte County, the Shawnee Indian Mission installed a new marker commemorating the original Shawnee Methodist Mission, though history buffs might have a hard time checking it out.

Forbes said access to the marker was designed to be from the dead end of 52nd Street, but he indicated in an email that “one has to look around a couple of fences on the dead end with good glasses” and still won’t see much of the marker.

We can only hope this memorial won’t suffer the same fate as its 1917 predecessor.

“You really hate to see things of that nature lost,” Forbes said. “I’m glad we were able to save the plaque before it was melted down for scrap.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.